“The paradox of education is precisely this— that as one begins to become conscious one begins to examine the society in which he is being educated. ”

Student Assessment

Assessment of Student Learning

Student performance and achievement is not ever fully captured in a letter grade. My first year of student-teaching I focused on the exact weights of participation, quizzes, written papers, presentations, discussion posts, and many other components. I thought that by having grading criteria clearly outlined and concise rubrics, students would be better equipped to succeed. I quickly realized grading must be as robust as student learning and must recognize the varied systems of education to truly capture learning growth. Below I will outline classroom assessment techniques (CATs) and strategies I use to evaluate students in the classroom and out-of-class assignments. Then I will speak to how COVID-19 is transforming remote learning and what I believe are aspirational grading methods warranted by this change.

Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs)

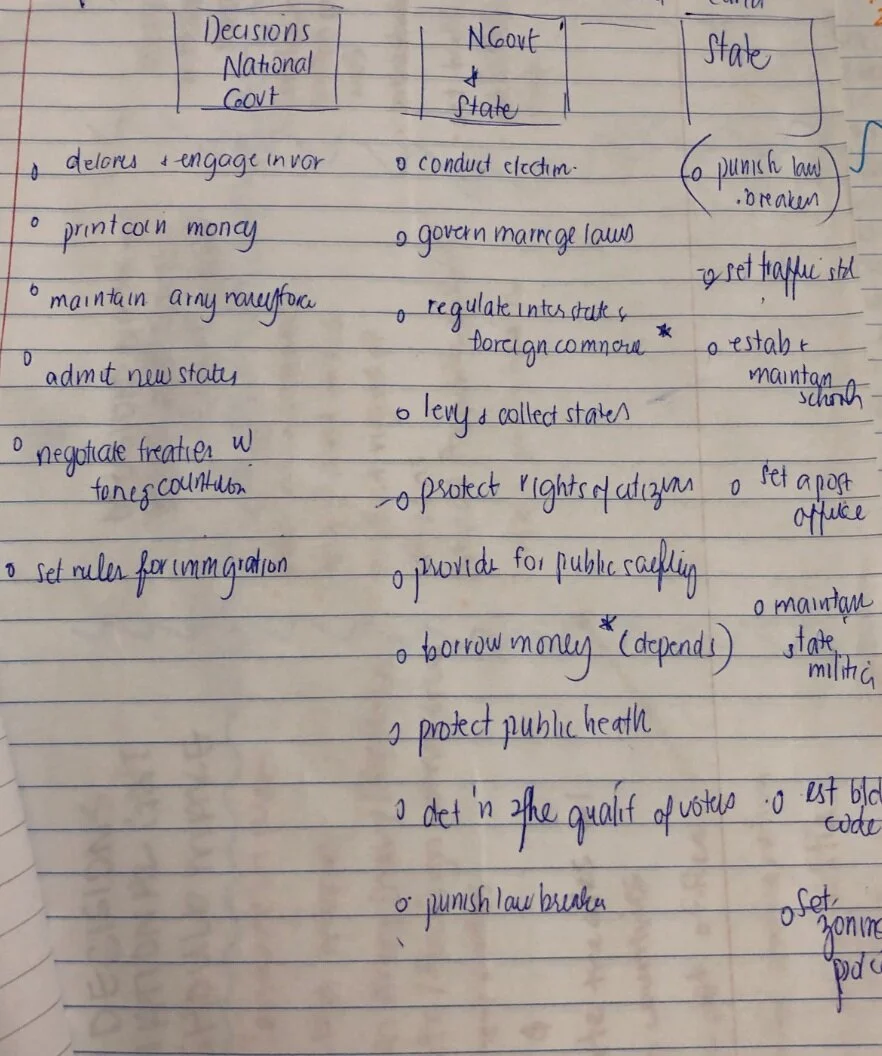

A defining feature matrix exercise using the concept of federalism.

When in the classroom there are several strategies I use to assess student mastery of the material. I enjoy beginning my lectures by storytelling, adding an anecdote, or sharing a case study. In this warm-up phase, as I like to call it, I tend to layer in background knowledge probes within the classroom. Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching calls these probes a short, simple questionnaire given to students at the start of a course or before the introduction of a new unit, lesson or topic designed to uncover student’s preconceptions. Although, I do not always provide these probes in the form of a questionnaire, I do inquire about the topic at hand and allow space for open discussion about the scenario discussed.

For example, when I teach students about federalism my 101 class, I begin the discussion through a defining feature matrix. A defining features matrix is a handout of three columns and several rows (Cult of Pedagogy). At the top of the first two columns, I ask students to distinguish between the functions and responsibilities at local, state, and federal levels of governments. As one would imagine, some functions seem straight forward, but as students begin to question the government's role in dealing with market failures and externalities, they begin to realize how muddled these functions can be in reality.

Similarly, when teaching Introduction to Latin American Politics, I realize many students have not actually visited the vast diversity of countries. I have two strategies to familiarize students with the region. First I do a map test. Although a map test seems elementary for a university course, the geographical spatial location is crucial to understanding the context and rich history of each region. This helps me understand how well students can navigate and distinguish the different countries. I usually connect this first-day of class exercise with assigning students to either individual or group presentations focused on introducing the institutional structures, society, and economic structure of one Latin American country. This assignment not only allows students to get a review of each country through the lens of other students, but I know from day one students have a country they can contextualize the broader lessons and become intimately familiar with.

Latin-America economic structure activity on a hypothetical country.

When students learn about economic patterns and structures in Latin American, I ensure they capture the neo-colonial influence of exports and resource-based economies. I make use of a game where each student receives a random deck of cards signaling their economic portfolio. Those cards determine the resources and wealth in each hypothetical country which then they must decide how to structure their budgetary and investment/debt portfolios. Students quickly learn the how the resource endowments of each country influences agency in the given global framework given.

Participation in the Classroom

The participation grade has often been found to be a subjective percentage of students' grades that can often be reduced to “impressionism” (Bean & Peterson 1998). Rigid attendance standard or cold-calling on students can be a dreadful experience that simply doesn’t work for all learners and can actually reinforce inequality. While I recognize the ongoing dilemma with accounting for participation, I believe that if structured correctly participation points have the ability to make students' engagement valued and visible.

In my courses, engagement means more than attendance. I think of participation as quality in-class interaction with the material and classmates. Whether I’m teaching online or in-class, participation can be a core method by which students enter into a social contract and govern themselves. Through participation students learn about the importance of civility and sharing space (see community guidelines in teaching philosophy statement).

Reading and unpacking Bitter Fruit.

Whether teaching online or in class, I always incorporate discussion boards. Discussion boards are another mechanism by which students are promoted and empowered as knowledge creators themselves. This allows students to connect with one another. I use the discussion boards as a way to add more personal context and facilitate idea creation to normative questions at hand. For example, when I teach about public opinion in my US Politics course, I like students to personalize this message. I have them interview a family member, friend, or associate so that they can begin to connect how personal experience tends to impact people’s perspective on politics. Students gain significant insight from this exercise that they can then apply when going through assigned readings. I find that this exercise allows the complexity of public opinion to better simmer in student’s minds.

Photo Credit: Patrick Perkins @pperkins

Techniques for Engagement

In order for participation to be accessible for students, there must be a diverse range of engagement opportunities for both discursive and quiet learners. Personally, this has been an ever-evolving process of trial and error, but along the way I have found a few strategies worth keeping for in-class participation.

10-minute check-in/unpacking headlines—Disorienting political times create real emotional and physical impacts to students. I began teaching amidst the 2016 presidential elections. I found that students were frequently distracted with what was going on in real time. So to alleviate feelings of angst, each class session began with a check-in and discussing headlines. I found this allowed students to make sense of events and refocus their attention to underlying lessons of institutional structure and epistemological outlooks of democracy. I found this as an effective strategy, especially if accompanied by a free-write for 2-3 minutes.

Create space for sharing—I find that creating opportunities for students to share their homework or research is a simple way to allow participation and make assignments connected to class conversations (Almagno 2017).

Think pair share—This collaborative learning strategy leads to active learning by facilitating students to first speak intimately with another classmate about the topic at hand. This requires students to focus attention and engage with each other. Afterwards, all students share back to the larger class group. By the time students share back, they already feel more comfortable to either clarify their questions or demonstrate command of the topic (Cult of Pedagogy)

Gallery walk—After reading a case study, article, or going through a book review a gallery walk is a helpful way to tease out themes, discuss ideas, and situate characters. Students are supplied with markers and wall-stick pads document what their initial group discussed. Then I rotate a few students in each group until all students are able to see each other’s work. This is a useful way to cover a range of topics and prepare students for a more meaningful class discussion (Cult of Pedagogy).

Affinity mapping—When I introduce a new concept or a big idea in the form of a question, I like to break up the topic by doing affinity mapping. I equip students with small post notes (one idea per sticky) then on the whiteboard allow students to put their ideas in no particular arrangement on the boards. From those initial ideas, I have students begin to group the stickies in similar categories. From there students can more easily label categories and begin to discuss why ideas fit together and relate to each other. This usually facilitates a much easier transition into a large topic (Cult of Pedagogy).

In-Class Grading Structure

In my syllabi you will find a grading structure usually combined of discussion boards, quizzes, written paper assignments, and at times midterms. As mentioned above, discussion boards are a core component in most of my classes. I find that they give space for students to interact and to tackle current events or material that is not necessarily captured in our textbook. The nature of the courses I teach are political in nature and this is one place where as a class we rely on our mutually agreed-upon community guidelines. When topics may be triggering for students, I provide options so that students are not all wedded to a single topic.

Test-anxiety is a serious issue that several experts find creates a significant stable and negative impact on academic performance (Cassady & Johnson 2002). Yet, quizzes can be a useful way to ensure students are keeping up with readings and are capturing basic learning concepts. To reduce anxiety related to quizzes, I have made my tests online, short, untimed, and open-book. I have considered adding a timing component to quizzes to ensure students have read the materia, but I have opted to err on the side of accommodation.

When I include a midterm exam, I provide students with a study guide. I have experimented with making review of the study guide a fun exercise. For example, in one of my courses I created a Bingo midterm review and compiled several prizes for winning students. I found this was one way to make learning exciting.

I incorporate writing assignments into all of my courses. I personally enjoy reading through student’s work and witnessing how they have made sense of the material. I tend to supply students with assignment instructions and create a basic grading rubric that I share with students ahead of time. To reduce the bias of impressions, I do blind grading. In my rubrics you will notice grammar and clearness is a component of the overall grading weight. However, as long as the overall message is clear, I refuse to be punitive on grammatical errors. I structure in my syllabus several opportunities to receive extra credit on written assignments. Particularly, if a student shows proof of visiting the writing center, I automatically give a couple percentage points on top of their grades.

COVID-19 Transformation of Remote Learning & Grading

It is ever more important to refocus on equity so that we do not consequently grade privilege during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Garcia (2018) privilege refers to certain unearned social advantages, benefits, or degrees of prestige and respect that an individual has by virtue of belonging to certain social identity groups who have traditionally occupied positions of dominance over others. The closing of schools, spiking unemployment levels, and fear of exposure for essential workers during COVID-19 makes conversation about race, power, and privilege in classroom grading ever more relevant. During these unprecedented times it is ever more important to encourage student learning through alternative assessment options.

The A-F letter grade system is a relatively new phenomenon that as late as 1971 only became widely practiced in primary and secondary schools as a way to create uniformity and improve reliability (Schinske & Tanner 2014; Schnider & Hutt 2013; Smallwood 1935). The dominance of standardized testing and the letter grade system can be traced back to eugenics based on the “fathers” of the curriculum that believed “innate capacity of the brain was inherited...many believed that the world’s darker-skinned races were inferior in intelligence than lighter-skinned ones, testing provided the moral equivalent to absolution when it came to access to education, and by extension, wealth and power” (Lemann 1999 in Winfield 2004). Testing as a tool in education is linked to our colonized past in that it was heavily influenced by the “Puritan attraction to improvement of the human state through system and order'' (Lemann 1999, page 18 in Winfield 2004).

Today, grading systems remain a controversial topic, even though our collective memory often slips on remembering this racist legacy nestled within our education system. Some of the most important arguments against A-F grading is that it plays on students fears of punishment and shame, diminish intrinsic motivation and enjoyment in class work, increase anxiety, among many other factors (Pulfrey et al. 2011; Harter 1978; Butler and Nisan 1986 in Schinske & Tanner 2014).

When discussing grading structures, educators regard feedback on performance as the essential component that can influence learning. Although grading itself is a form of evaluative feedback, unless it is also accompanied by descriptive feedback, it can distract from learning and leave students feeling disengaged with no understanding of how to improve (Schinske & Tanner 2014). Over the next few courses I’d like to experiment with more qualitative feedback and evaluation. Using Portland State University’s Office of Academic Innovation, I will outline two methods in which I can implement evaluative feedback.

The 5-point System—Students receive 5 out of 5 points for every assignment if it is submitted on time, follows directions, does the work correctly. Student’s receive feedback throughout the term via peer-review, instructor comments, self reflections, and comparing work to exemplar pieces. I experiment with some of this grading already in discussion boards and see it as an avenue for grading written work.

Student Self-Assessment—Requiring a paradigm shift, this method requires that the instructor and student both believe they have the agency to determine their own grade and the instructor must trust the student’s capability of doing so fairly.

Currently, I am considering adopting a policy blog-style contract for my students in a way that their work is incremental and amounts to a portfolio they can keep years after they have left the classroom. This is a way students can exhibit their work in a cohesive and less stressful manner—by assigning smaller projects that amount to a whole. In addition, knowing how to navigate and maintain an online presence has become essential to any work function in political science and public administration that some students may actually find familiar and even therapeutic. I will report back once I implement these techniques. Wish me luck.

Resources

Bean, J. C., & Peterson, D. (1998). Grading classroom participation. New directions for teaching and learning, 1998(74), 33-40.

Butler R, Nisan M. Effects of no feedback, task-related comments, and grades on intrinsic motivation and performance. J Educ Psychol. 1986;78:210.

Cassady, J. C., & Johnson, R. E. (2002). Cognitive test anxiety and academic performance. Contemporary educational psychology, 27(2), 270-295.

Cult of Pedagogy. 2020. Cult Of Pedagogy. [online] Available at: <https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/> [Accessed 7 August 2020].

Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. 2020. Participation Points: Making Student Engagement Visible. [online] Available at: <https://www.facultyfocus.com/articles/effective-teaching-strategies/participation-points-making-student-engagement-visible/> [Accessed 7 August 2020].

García, Justin D. 2018. “Privilege (Social Inequality).” Salem Press Encyclopedia.

Harter S. Pleasure derived from challenge and the effects of receiving grades on children's difficulty level choices. Child Dev. 1978;49:788–799.

Lemann, Nicholas. The Big Test: The Secret History of the American Meritocracy. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1999. In: Winfield, A. G. (2004). Eugenics and education: implications of ideology, memory, and history for education in the United States. North Carolina State University.

Office of Academic Innovation. 2020. Encouraging Student Agency Through Alternative Assessments - Portland State University. [online] Available at: <https://oaiplus.pdx.edu/portfolio/encouraging-student-agency-through-alternative-assessments/> [Accessed 7 August 2020].

Pulfrey C, Buchs C, Butera F. Why grades engender performance-avoidance goals: the mediating role of autonomous motivation. J Educ Psychol. 2011;103:683.

Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching more by grading less (or differently). CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159-166.

Schneider J, Hutt E. Making the grade: a history of the A–F marking scheme. J Curric Stud. 2013:1–24.

Smallwood ML. An Historical Study of Examinations and Grading Systems in Early American Universities: A Critical Study of the Original Records of Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, Mount Holyoke, and Michigan from Their Founding to 1900, vol. 24. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1935.

Vanderbilt University. 2020. Classroom Assessment Techniques (Cats). [online] Available at: <https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/cats/> [Accessed 7 August 2020].

Winfield, A. G. (2004). Eugenics and education: implications of ideology, memory, and history for education in the United States. North Carolina State University.